This piece is based on a presentation given to fellow PhDs at the University of Agder on 29 November 2023. The brief for the presentation was to present my own research to a lay audience attending UiAs popular dissemination series, Lørdagsuniversitetet.

When I started as a PhD at the University of Agder, and my friends and family would ask what I would be researching and when I answered “subtitling”, it turned out to be quite a good conversation starter. Turns out that since Norwegians have a lot of experience with subtitles (some estimate that the amount of subtitles we consume per year estimates 1400 pages of literature per year[1]) they also have quite strong opinions on the subject. But not just any subtitles, people rarely talk about a particularly well subtitled programme, but we seem to remember and love to talk about the bad subtitles. So, safe to say, some of my friends and famlily seemed almost disappointed when I told them that I would not be spending three years identifying mistakes in subtitles and pointing out to the translators what went wrong in the process and that they should get their act together.

Instead, I spend my time looking into getting more insight into how subtitlers deal with certain features of our language and if the finished subtitles can teach us something about how subtitlers process the information given to them through spoken dialogue, the images on screen and the overall narrative. In order to do this, I have chosen to focus on a fun little feature of language and thought that we call metonymy. Now, many of you have probably already heard of metaphor, and acquainted yourself with metaphor analysis in fiction and poetry, whether it was by your own free will or being forced to do so in school.

Although metaphor and metonymy are in many ways similar, the main difference is that whereas we use metaphor to create novel images comparing for example red cheeks to rose petals, in metonymy we use one part of for example an object to describe or make reference to that same object.

Such as the title of the movie Jaws in which we use part of the shark, namely it’s mouth, to describe the main antagonist of the movie. The jaws of a shark is particularly striking image that is bound to invoke a sense of foreboding or dread on audiences. One could also argue that «Jaws» is far more striking than if the movie had just simply been called «Shark», and this also shows us how metonymy can be effective as a rhetorical device.

Metonymy is not only restricted to written or spoken language, but also found in visual images. If we look at the poster for Jaws, we only see the head where the teeth are the most prominent feature, instead of the whole shark. And whenever you see an image of a shark fin gliding across the water surface and you think of the shark lurking underneath the surface, that is also an example metonymy. Commercials are also a good source of visual metonymies, e.g. when you see a commercial for fizzy drinks, we often see the image of the bottle or can, but the point isn’t for you to want to buy the bottle, but what’s inside of it. In other words the image of the can or bottle, invokes the contents of the container.

Returning to Jaws one last time: metonymy can also occur in sound, and John Williams’ chilling theme from the movie is a particular good example of this. The dissonant two chord theme has become so closely associated with the image of the shark, that instead of saying «shark» you could just sing that theme instead[2].

Where does metonymy come from and what allows us to use it in communication? Back in the late 70s and early 80s a group of linguists began to look deeper into how we use metaphor and metonymy in our daily language[3], and what they discovered is that we use it so frequently that we don’t even realise it most of the time. This tells us that both metaphor and metonymy is a central feature of our cognition and way of thinking.

Imagine that your brain is made up of lots of little boxes, each box representing some part of your knowledge about people, things, events, places and so on. Our ability to link this information with each other is what allows us to use things such as places and names as metonymies, think for example of how we say «Westminster» when referring to the British government or «Wall Street» as a name for several financial institutions. That’s because our knowledge tells us that these things are connected to each other, Westminster is where the government of Britain sits, and Wall Street is where the biggest banks are located.

Metonymy is grounded in our experience, when we meet and interact with people, objects, places, and events, our interaction with them allows us to use properties and parts of these to speak of the whole or even parts to describe parts. It helps people with shared interests and knowledge to communicate effectively. Think for example of people working in a specialised profession such as medicine, where doctors will use jargon and medical terms between themselves as a group, but they will most likely use a different type of language when talking to their patients. Think about your own work, how do you talk with your colleagues, or how do you talk with close friends? In social settings, metonymy can help us build relationships with people whom we share experiences with.

How is the knowledge of metonymy, how we use it and situations where it might occur, relevant to translation? Since metonymy is often closely tied to specific discourse communities, they do not necessarily travel well across linguistic and/or cultural borders, and they therefore become problems that a translator needs to solve. The translator is in one way the outsider that is trying to get access into the discourse community by figuring out what is said. To do this, they need to be able to access the same mental box that the metonymy originated from and make the proper connections in their own language

The point of subtitling is not to translate just what is being said, but what is the overall meaning of the story being told on screen, and this creates a contract of illusion where the viewer is able to follow the narrative on screen with as little awareness of the subtitles as possible.

In addition to paying attention to the dialogue, the subtitler must always keep in mind what is happening on screen, such as who is speaking; where are they; what tone of voice are they using; what kind of situation do they find themselves in? Since metonymy is such an integral part of our way of communicating with each other, it can often be difficult to make the distinction between literal or figurative meaning, and therefore the context becomes important to figure the intended meaning.

Because if there is a mistake (and this doesn’t just happen with metonymy and metaphor) then there is a disconnect between what the viewers hears and sees and what it says in the subtitle, and the contract of illusion between viewer and subtitler is broken. This is probably why we notice the mistakes more than we notice the good subtitles. However, if the subtitler is able to piece the puzzle together correctly, then the job is done and hopefully, the viewer will be able to enjoy the programme without noticing the subtitles more than necessary.

To finish, I will illustrate how metonymy can be dealt with in subtitling with an example from the comedy series “Veep” (2012-2019).

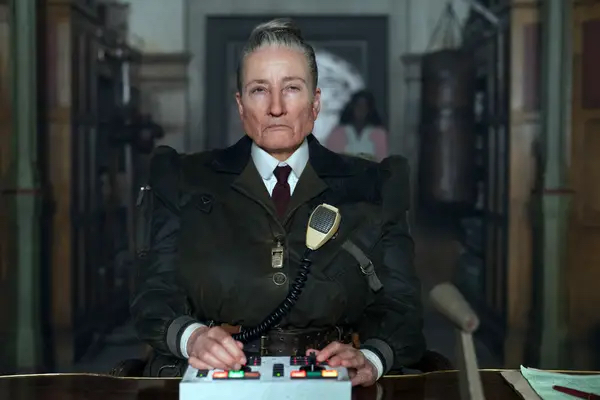

Here is a screenshot showing the English dialogue:

In this example we have two instances of metonymy, first “park” which according to the dictionary (e.g. Collins Dictionary[4]) is used to refer to a baseball stadium. The second metonymy is the name “Shoeless Joe”, which is the nickname for the baseball player Joe Jackson who was central in a game fixing scandal in the 1920s. The whole exchange is a reference to the character being addressed being a former baseball player, and not a particularly good one. Since baseball is not a major sport in Norway, the subtitler therefore has to make the decision whether to keep the terminology and the nickname or choose a different approach, such as finding an equivalent in Norwegian or leaving the name out altogether.

As we see from the Norwegian subtitles, the subtitler chose to replace “park” with “tribunen” (lit. the stands) and decided to leave the nickname out altogether. My guess would be that most Norwegian viewers would have no problem with this translation, and would probably have wondered more if the name was kept in its original form or replaced with a Norwegian equivalent.

References

[1] NRK (2023) Maskinene har begynt å oversette film og TV. (https://www.nrk.no/kultur/gode-oversettelser-blir-oversett-pa-strommetjenestene-1.16199448. Accessed 26 Januar 2023)

[2] https://www.classicfm.com/composers/williams/music/jaws-theme/

[3] George Lakoff and Mark Johnson’s Metaphors We Live By (1980) is one of the most seminal works in this line of research.

[4] https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/park